A guest post by Bonnie Bright, Ph.D.

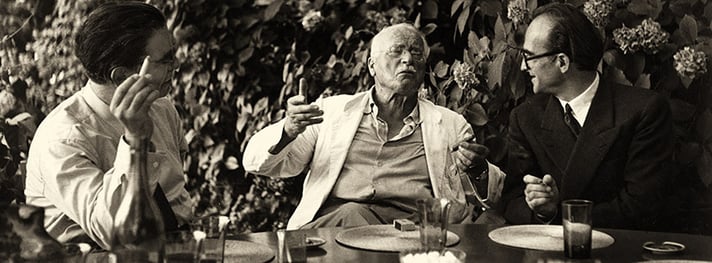

Dr. Lance Owens has dedicated the past thirty or more years of his life to studying C.G. Jung, whose willingness to engage with and understand his visionary experiences has transformed so many lives. Owens has also recently become profoundly interested in the life and work of Erich Neumann, who was arguably one of Jung’s most gifted students, and who eventually became a close friend of Jung’s. Through the influence of Jung, Neumann made his own creative and compelling contributions to the field of depth psychology through works such as The Great Mother (1955), The Origins and History of Consciousness (1954), and Depth Psychology and a New Ethic (1949) among others.

Lance Owens’ interest in Neumann was amplified by the publication of letters between Jung and Neumann in 2015, correspondence that revealed the tremendous respect Jung had for his friend and for the Neumann’s capacity to grasp many of the depth concepts that were so critical to Jung for his own reasons. In fact, Owens’ himself has also uncovered such a deep regard for Neumann that in a recent email to me, he wrote quite poignantly, “Neumann has become one of those ‘dead friends of the soul’ that come to help and haunt us, with their questions, and their answers, and the facts of their own lives. I do now believe that hearing Neumann’s voice, across the decades, is a crucial event in understanding the development of Jung’s movement, and of Jung’s own experience.”

During our recent conversation, Lance explained how Neumann, having grown up in an integrated German family in Berlin, realized in his twenties that there was no place for him in German culture. Rather, he embraced his Jewish roots in spite of not being a practicing Jew. When Hitler took power in 1933, Neumann left Germany for Israel, stopping over in Zurich for six months in order to spend time in analysis with Jung.

As Lance views it, this was part of an initiatory phase for Neumann. He was, perhaps, looking for tzadik[i], a spiritual guide, when he went for analysis with Jung. During Neumann’s quest for his Jewish roots, he had been intrigued by Martin Buber’s writings on Hasidism[ii], which was centered around renewal and spiritual energy. Hasidism, a movement that emerged in the eighteenth century, was led by a mystical rabbi, Israel ben Eliezer (also called Baal Shem Tov), widely considered to be the founder of Hasidism.[iii] Neumann believed that ben Eliezer and his successor, the Mezritcher Maggid, had found a transparency between the outer and the deeper realities, enabling them to see through, to perceive the Divine in the world.

Neumann seemed to find in Jung the tsaddik he was searching for, a unique leader who also had the ability to see through the world to the depth in a similar way. In accordance, Lance Owens informs me, Neumann, after those six months of analysis with Jung, affirmed for the remainder of his life that it was the transformative event of his life and he could not imagine what his life might have been without that experience.

Once Neumann arrived in Israel, he established depth psychology there. While today’s training to become a Jungian analyst can be quite intensive and drawn out, Owens points out, Jung had one primary for someone to become a Jungian analyst: the analyst-in-training must know the psyche was real. Neumann most certainly got that, Owens insists.

Upon his arrival in Israel in 1934, Jungian psychology was still new to Neumann, but he did his best to establish his practice based on what he knew. Though he returned more than once to visit Jung in subsequent years, by 1939 when World War II began in earnest, correspondence between Jung and Neumann was completely cut off until 1945 after the war was over. During that time in Israel, Neumann was seeing patients, sometimes up to 50 hours a week, many of them victims of the Holocaust with very little money, but a great deal of trauma that needed to be addressed. Neumann’s patients were dealing with issues of the Jewish spirit, Lance affirms.

Neumann was very isolated during the period of time he was on his own in Israel. In fact, as Owens notes, the Jung-Neumann letters are subtitled, “Analytic Psychology in Exile,” and Neumann was very much in exile. While most of Jung’s followers had the benefit of remaining with him throughout the war years, Neumann, having no other choice, took what he learned from Jung and applied it, imagined into it, and expanded it in ways that occurred to him as he went along. When Neumann was finally able to return to Zurich in 1946, he had written massive amounts of content, including the beginning of Depth Psychology and a New Ethic and Origins and History of Consciousness, among others. Neumann took the entrée that Jung had given him, to accept that the psyche was real, and he talked and wrote about it.

When Neumann and Jung reconnected after World War II ended, Jung was deeply appreciative of the extent of Neumann’s creative application of depth psychology, Owens relates. Neumann’s book, Depth Psychology and a New Ethic, focused on encountering the shadow in ourselves that we see in the “other,” and Jung praised it highly. When Neumann sent Jung a copy of Origins and History of Consciousness, Jung deemed it “brilliant.” As Owens shared with me, he is aware of the work of no other whom Jung praised as directly as he did that of Erich Neumann.

Jung’s own lifelong work began to manifest in his writings in the Liber Novus, also known as The Red Book, beginning in 1913 and continuing through World War I until 1918 or 1919. The work revealed that Jung felt the Christian age was coming to an end, an idea Lance Owens investigates in his own paper entitled, “Jung and Aion.”[iv] Jung saw that there was a two-thousand-year transformation taking place in human consciousness, Owens asserts. New God images were forming. Jung felt we needed to come into a new relationship with the “depths,” with the psychic realm. There were things “bubbling up—in us, through us, in our cultures” —as Owens puts it.

Jung fully engaged those questions throughout his life, even though he was not necessarily quick to communicate them. For a long while he said he did not think he could share the “secret knowledge” he had acquired, though some of that changed in 1944, when Jung had a series of visions after he had a heart attack resulting in a near-death experience.

Owens notes that both Jung and Neumann felt that humanity was on the edge of a great transformation. Jung felt a deep connection to his tradition, his “dead,” his Christian history, Owens insists, and at the same time, Neumann approached things from his tradition as a Jew. However, they both came to many of the same conclusions, and both focused on two core issues: the question of evil, and the forgotten or repressed feminine.

The visions that ultimately became The Red Book (which many Jungians still have not studied, Owens notes wryly), contributed to Jung’s recognition that the subject of “evil”—the dark one, the shadow, the mercurial figure, the “other”—was tremendously forgotten in Christian theology. In Judaism, this shows up in the concept of the yetzer hara[v]—defined as “the inclination to evil,” Owens suggests. Jung understood that the understanding of evil had to be incorporated in our coming conscious understanding of what it means to be human.

The second issue Jung wrestled with was the forgotten feminine—the “in-dwelling imminence of a transcendence in this world”—the idea of guides, Lance believes. Neumann, too, had encountered the forgotten or repressed feminine in Judaism in the face of patriarchy. He pulled from Jewish psychology the image of the Shekinah[vi], the divine feminine or the feminine element of the transcendent which dwells in the world, but which has been exiled.

Jung’s idea of the coming consciousness involved not only a recognition of evil and of the feminine, but also of a coniunctio in consciousness, a union of inner and outer, of “sense and nonsense,” between bright and dark, and between masculine and feminine elements. Jung began to really write about them after his illness in 1944, in Aion, An Answer to Job, and Mysterium Coniunctionis, and it was during this period that Jung truly found he could talk to Neumann about the issues most critical to him. While it is possible Neumann saw parts of The Red Book and had probably even discussed some of Jung’s experiences and findings, Neumann had come to many of the same conclusions through working his own process and through his own perspective which was, in many ways, parallel to those of Jung.

We each come to those universal truths in our own way, Lance insists. Finding what’s authentically ours involves us each going in to our history, our psychic history and our heritage. This heritage can come in dreams or visions, without any cognitive planning of the process. Neumann came to his own myth authentically through his own tradition in mystical aspects of Judaism, allowing him to engage and dialogue very profoundly with Jung’s own psychology in so many ways.

Dr. Lance Owens is speaking at “Creative Minds in Dialogue: The Relationship between C. G. Jung and Erich Neumann,” a symposium at Pacifica Graduate Institute in Santa Barbara, CA, June 24-26, 2016, alongside several other internationally acclaimed speakers including Murray Stein, Lionel Corbett, Nancy Furlotti, Ann Lammers, Rina Porat, Susan Rowland, Evan Lansing Smith, Steve Zemmelman, Riccardo Bernardini (of the Eranos Foundation in Switzerland, where both Jung and Neumann were actively engaged), and Erel Shalit, who is a Jungian analyst based in Israel and who hosted a conference on the recently published Jung-Neumann letters there last year in 2015.

Listen to the full interview with Lance Owens here (Approx. 35 mins.).

Learn more/Register for the symposium at http://www.pacifica.edu/current-public/item/creative-minds-in-dialogue

[i] A tzadik (also spelled zadik or sadiq) refers to a spiritual master: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tzadik

[ii] See Martin Buber’s works such as The Tales of Rabbi Nachman, The Legend of the Baal-Shem, and Tales of the Hasidim

[iii] Israel ben Eliezer, the founder of Hasidism, was also known as the Besht, or Baal Shem Tov, a Jewish mystical rabbi: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baal_Shem_Tov

[iv] “Jung and Aion: Time, Vision, and a Wayfaring Man” by Lance S. Owens is available to read at http://www.gnosis.org/Jung-and-Aion.pdf

[v] Yetzer hara, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yetzer_hara

[vi] Learn more about the Shekinah the Jewish Virtual library at http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/Shekhinah.html

Lance S. Owens is an historian and a physician in clinical practice. He has served on the clinical staff of the University of Utah for over two decades. Since publication of Jung's Red Book: Liber Novus in 2009, Dr. Owens has published several studies focused on Jung's extraordinary visionary experience. His lectures and seminars on Jung and the Red Book (available online) have been enjoyed by many thousands of listeners. Dr. Owens is also the founder and editor of “The Gnosis Archive”, the major Internet repository of ancient Gnostic texts, including the complete Nag Hammadi Library of Gnostic Scriptures. A catalog of his publications and audio lectures is available at: www.gnosis.org/Lance-Owens

Bonnie Bright, Ph.D., graduated from Pacifica’s Depth Psychology program in 2015. She is the founder of Depth Psychology Alliance, a free online community for everyone interested in depth psychologies, and of DepthList.com, a free-to-search database of Jungian and depth psychology-oriented practitioners. She is also the creator and executive editor of Depth Insights, a semi-annual scholarly journal, and regularly produces audio and video interviews on depth psychological topics. Bonnie has completed 2-year certifications in Archetypal Pattern Analysis via the Assisi Institute; in Technologies of the Sacred with West African elder Malidoma Somé, and has been extensively involved in Holotropic Breathwork™ and the Enneagram.

Bonnie Bright, Ph.D., graduated from Pacifica’s Depth Psychology program in 2015. She is the founder of Depth Psychology Alliance, a free online community for everyone interested in depth psychologies, and of DepthList.com, a free-to-search database of Jungian and depth psychology-oriented practitioners. She is also the creator and executive editor of Depth Insights, a semi-annual scholarly journal, and regularly produces audio and video interviews on depth psychological topics. Bonnie has completed 2-year certifications in Archetypal Pattern Analysis via the Assisi Institute; in Technologies of the Sacred with West African elder Malidoma Somé, and has been extensively involved in Holotropic Breathwork™ and the Enneagram.