Photography: Into the Heart of Traditional Cultures in Times of Global Change. An Interview with Writer and Photographer, Michael Benanav, M.A. A Guest Post by Bonnie Bright, Ph.D.

Michael Benanav is a critically-acclaimed writer and photographer who has traveled to a lot of places that are well off the beaten path, often finding himself in remote mountains and landscapes, walking, being in nature, and living quite simply. There, in the wilderness, he often runs into nomads, and he quickly became fascinated by their way of life. Benanav, whose work has appeared in publications like The New York Times, Geographical Magazine, Lonely Planet Guidebooks, and CNN.com, was naturally drawn to spending time with them.

These profoundly archetypal lifestyles inevitably appear in Benanav’s work. In his first book, a travel narrative entitled Men of Salt: Crossing the Sahara on the Caravan of White Gold (2008), he joined one of the last working camel caravans in the world, which runs an ancient salt trading route in the Sahara desert in Mali. Leaving Timbuktu, the route veers 500 miles north into the vast desert to salt mines located “in the middle of nowhere,” hundreds of miles away from any village. There's no electricity, no telephone; not even fresh water, Benanav reports.

These profoundly archetypal lifestyles inevitably appear in Benanav’s work. In his first book, a travel narrative entitled Men of Salt: Crossing the Sahara on the Caravan of White Gold (2008), he joined one of the last working camel caravans in the world, which runs an ancient salt trading route in the Sahara desert in Mali. Leaving Timbuktu, the route veers 500 miles north into the vast desert to salt mines located “in the middle of nowhere,” hundreds of miles away from any village. There's no electricity, no telephone; not even fresh water, Benanav reports.

Benanav landed upon the idea of joining the caravan when doing some research for a project he was working on in Mongolia that involved investigating the evolutionary advantage for some camels have one hump and others to have two. He became completely energized when he stumbled across information about the caravan, and somehow knew he could tell this story that had really never been told before.

It was only when he arrived in Timbuktu and started talking people that he was able to arrange camels and caravan drivers that would allow him to embark with the caravan. And while his primary aim was to write the story, he also worked alongside others in the caravan, loading or unloading salt, helping feed and water the camels, or even taking the camels on ahead while his Muslim companions took the time to stop and pray when the sun rose.

Benanav admits he experienced anxiety about coming face to face with the sheer human destitution he was sure to encounter, in a community of men who spend all day cutting salt out of the ground in the middle of nowhere for very low wages. And yet, he was caught by surprise. What he found instead was a group of people who really knew how to “squeeze every ounce of joy out of every possible moment they have.” They were constantly laughing, joking, dancing, singing, and playing around, he notes. “It was quite incredible to be able to find so much appreciation for life in a place that was so bleak.”

Through his experience, Benanav made some astute observations about the cultural differences that are so glaringly apparent between the United States and countries he has traveled to. If you're in Africa or you're in India, you simply can't get impatient waiting in line, he points out, whereas in the U.S., sometimes waiting for five minutes feels like a crisis. Getting out of the U.S. and immersing oneself in a different perspective can really create an important paradigm shift, and Benanav has done this time and again since he first got his Master’s degree in Counseling Psychology from Pacifica. That degree has played a critical role in his work, both with the caravan and the salt miners, as well as some of the other experiences he has encountered. Once you've studied depth psychology, it becomes your worldview, a part of who you are, he points out. It affects everything in terms of the way you perceive things, as well as the way you tell stories.

More than that, there are a lot of “heart skills” from the counseling program that have been incredibly useful. Benanav, who frequently finds himself talking to a variety of people and trying to understand their lives and stories, finds a lot of overlap between good journalistic technique and good counseling technique.

It's really crucial to not make assumptions that you know what their lives are like, he asserts. Asking the kind of questions that you would ask in counseling or even reflecting back to them so you're sure you know what they mean is an incredibly helpful process for understanding their perspectives.

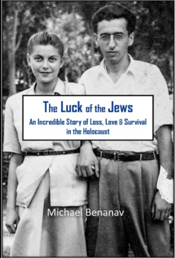

Benanav goes on to share the story of his second book, The Luck of the Jews: An Incredible Story of Luck, Love, and Survival in the Holocaust (2014), which details the story of his paternal grandparents and how they survived World War II in Eastern Europe. They ended up meeting each other on the deck of a refugee boat that was sailing across the Black Sea in December of 1944. Their story is one of those incredible survival stories where, if any one small thing had gone a different way in any aspect of their lives, everything would have turned out completely differently.

Benanav goes on to share the story of his second book, The Luck of the Jews: An Incredible Story of Luck, Love, and Survival in the Holocaust (2014), which details the story of his paternal grandparents and how they survived World War II in Eastern Europe. They ended up meeting each other on the deck of a refugee boat that was sailing across the Black Sea in December of 1944. Their story is one of those incredible survival stories where, if any one small thing had gone a different way in any aspect of their lives, everything would have turned out completely differently.

After sitting down with his grandparents once for a couple of hours and hearing his grandmother tell her story in some detail for the first time, he knew he wanted to engage more deeply. In addition to adding the historical context for the story, he also personally traveled to the places his grandparents referenced in order to see and experience them for himself. Ultimately, the story helped his own family understand where they came from.

While themes of home, ancestors, and tradition are readily apparent in Benanav’s work, his third and upcoming book is perhaps most focused on these themes. For Himalaya Bound: One Family's Quest to Save Their Animals and an Ancient Way of Life (set for publication in January of 2018), Benanav traveled to India and joined a family in a tribe of nomadic water buffalo herders. Each spring, the tribe migrates up into the Himalayas where they spend the summer, then migrates back down to the Shambolic Hills in the Fall.

While themes of home, ancestors, and tradition are readily apparent in Benanav’s work, his third and upcoming book is perhaps most focused on these themes. For Himalaya Bound: One Family's Quest to Save Their Animals and an Ancient Way of Life (set for publication in January of 2018), Benanav traveled to India and joined a family in a tribe of nomadic water buffalo herders. Each spring, the tribe migrates up into the Himalayas where they spend the summer, then migrates back down to the Shambolic Hills in the Fall.

Typically and historically, nomads rely on ancient survival strategies which involve knowing where to find grass so they can feed their animals. In today’s world, times have changed drastically because international or state borders have changed, or land where the nomads used to travel to now hosts farms, factories, or national parks.

Additionally, many nomadic people are really struggling with the effects of climate change because they're dependent on rain, which sustains the life-giving grass their animals need. When they can no longer access that vital grass, their age-old survival strategies no longer work. These people are part of an endangered culture, increasingly facing serious problems, year after year, Benanav maintains. He chose to document them because this way of life may completely disappear within a generation or two.

One of the archetypal themes that looms over everything is the idea of power, he notes. The most immediate threat for these particular nomads is that some of their traditional grazing lands have been turned into national parks. And as a result, many have been evicted, or face threats of eviction, from those areas because park authorities are enforcing boundaries put in place to conserve wildlife habitats. As national parks, nomads and buffalo are not allowed to live in and graze on those lands.

This conservation theory, which can be summarized as “no people in parks,” is rooted in a very Western way of looking at the world, Benanav points out. In this worldview, human beings can never be natural parts of environmental ecosystems; people are always invasive species. If you want to actually protect wildlife habitat, you have to separate people from nature.

From an indigenous perspective, those people have been living in those areas for hundreds or even thousands of years. They consider themselves an integrated part of the ecosystem; part of what keeps it in balance. They argue that removing them from the ecosystem would actually impact the environment more than allowing them to stay. But because Western ideas of conservation are so dominant, tens of millions of “conservation refugees” exist around the world after being evicted from their traditional lands. This is a power dynamic where Western mentality places itself over and above the indigenous way of thinking, Benanav declares.

Another depth psychological perspective is that there is a masculine way of doing things and a feminine way of doing things. These terms, used in a depth psychological sense, don’t necessarily refer to gender but more to modes of being. Living in touch with nature and earth, in tune with the cycles and the seasons, may be looked at as it is a feminine way of being while Western cultures have tended to adopt a more masculine approach that is more goal-oriented; more rational, linear, and focused on achievement. Depth psychology, in so many ways, enables us to find ways to bridge the two.

Going back to the topic of archetypes Benanav shares some of the more archetypally evocative places he has visited in his extensive travels. There’s something incredibly powerful about the desert, whether it's the Sahara, deserts in Jordan or Egypt; or even in Utah, where Benanav is speaking from at the time of our interview. He really resonates with these areas. And he feels at home in these places, while also being awed by them.

India is another place that is archetypally evocative. It’s truly unbelievable, he submits, in great part because there you are, constantly inundated by imagery of the gods and goddesses. They're very colorful in evocative ways. This kind of imagery stimulates my imagination, and I wonder how Benanav, also an accomplished photographer, perceives that the images he creates through his work have an impact on other people.

“I think my most powerful images are probably of people,” he offers. “Most of it has very little to do with any kind of photographic technique, and everything to do with having some ability to actually connect with the people and invite them, in some way, to reveal something of themselves, and then somehow being able to capture that in a picture.” For him, he feels his best work is when people who are looking at the photo can actually feel some kind of visceral connection to the person in the photo; that is, they get something, almost directly, from the person he has photographed.

I have to think that Benanav has succeeded in so many of his aims. Seeing the images or reading the narratives that burst forth from his work—work that is grounded in a depth psychological foundation—truly brings the stories to life and helps the history and traditions live on, at least for a little while longer.

Listen to the full audio interview with Michael Benanav here (approx. 28 mins):

Learn more about the Masters in Counseling Psychology program at Pacifica at pacifica.edu

Caravan and water buffalo photos are provided by Michale Benanav. Learn more about Michael Benanav at www.MichaelBenanav.com; www.traditionalculturesproject.org; and www.20shots.com Michael Benanav is a writer and photographer whose work appears in The New York Times and other publications. He is the author of three books, including his latest, Himalaya Bound: One Family’s Quest to Save Their Animals and an Ancient Way of Life, due out in January 2018. He often finds himself drawn to telling the stories of traditional and indigenous communities in far-flung places—particularly nomadic people. When he’s not traveling, he lives in northern New Mexico. He graduated from Pacifica’s MA Counseling program in 1998.

Michael Benanav is a writer and photographer whose work appears in The New York Times and other publications. He is the author of three books, including his latest, Himalaya Bound: One Family’s Quest to Save Their Animals and an Ancient Way of Life, due out in January 2018. He often finds himself drawn to telling the stories of traditional and indigenous communities in far-flung places—particularly nomadic people. When he’s not traveling, he lives in northern New Mexico. He graduated from Pacifica’s MA Counseling program in 1998.

Bonnie Bright, Ph.D., is a graduate of Pacifica’s Depth Psychology program, and the founder of Depth Psychology Alliance, an online community for everyone interested in depth psychologies. She also founded DepthList.com, a free-to-search database of Jungian and depth psychology-oriented practitioners, and she is the creator and executive editor of Depth Insights, a semi-annual scholarly journal. Bonnie regularly produces audio and video interviews on depth psychological topics. She has completed 2-year certifications in Archetypal Pattern Analysis via the Assisi Institute and in Dagara-inspired ritual and medicine with West African Elder Malidoma Somé, and she has trained extensively in Holotropic Breathwork™ and the Enneagram.

Bonnie Bright, Ph.D., is a graduate of Pacifica’s Depth Psychology program, and the founder of Depth Psychology Alliance, an online community for everyone interested in depth psychologies. She also founded DepthList.com, a free-to-search database of Jungian and depth psychology-oriented practitioners, and she is the creator and executive editor of Depth Insights, a semi-annual scholarly journal. Bonnie regularly produces audio and video interviews on depth psychological topics. She has completed 2-year certifications in Archetypal Pattern Analysis via the Assisi Institute and in Dagara-inspired ritual and medicine with West African Elder Malidoma Somé, and she has trained extensively in Holotropic Breathwork™ and the Enneagram.