A guest post by Bonnie Bright, Ph.D.

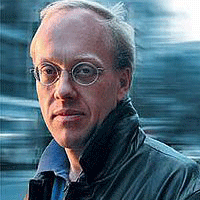

When I met Chris Hedges online for our recent interview together, I could see why Pacifica Graduate Institute invited him to speak at their milestone 40th anniversary celebration conference, Climates of Change and the Therapy of Ideas, which takes place April 21-24, 2016, in Santa Barbara, CA.

As a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, Hedges carries with him nearly two decades of experience reporting from war-torn countries like Yugoslavia, El Salvador, and also Gaza and South Sudan. In this capacity, he has witnessed the decline and disintegration of multiple societies, a perspective which has surely influenced his capacity regard the decline and potential destruction of our own modern culture that seems severely out of order.

He has been described, more than once, as being “dark,” which, from a depth psychological perspective, I’m quick to assure him, is actually a compliment. Depth psychology insists we look under the surface and in the margins of things in order to better understand them, and then requires that we witness and hold what we find in spite of the darkness from which we might easily prefer to flee. Chris appears to take this in stride: recognizing and carrying the knowledge that contemporary society is facing its own morbidity, in some ways, has fallen squarely on his shoulders.

Hedges notes that, as both individuals and civilizations, we encounter cycles of growth, maturation, decadence, and decay, and death. In contemporary society—especially modern society—we can see the signs of morbidity around us, in our boundless use of harmful fossil fuels, in much sought-after expansion beyond the capacity to sustain ourselves, and in the physical decay of the environment and in the places we inhabit.

Hedges notes that, as both individuals and civilizations, we encounter cycles of growth, maturation, decadence, and decay, and death. In contemporary society—especially modern society—we can see the signs of morbidity around us, in our boundless use of harmful fossil fuels, in much sought-after expansion beyond the capacity to sustain ourselves, and in the physical decay of the environment and in the places we inhabit.

There are common patterns and common responses to decline and collapse across eras and cultures. While our culture is more technologically advanced in comparison with that of Easter Island, for example, it is arguable that human nature has not really changed. Who was it that cut down the last tree on Easter Island, for example? He wasn’t thinking, Hedges asserts, and neither are we today! Since the Jungian viewpoint is that we are each on our own journey of individuation, increasing consciousness and moving toward wholeness, for me, Chris’s point raises the question as to whether our culture should actually be individuating as well—but is somehow stuck in its process.

How is it that most of us, myself included, are able to go about our daily lives engaging in habits and participating in systems that are destroying the planet, harming each other, and generally contributing to the detriment of society? There is a psychological mechanism by which people seek to blind themselves, Hedges insists. We tend to cling to a belief system that essentially shuts us off, disconnects us from what’s actually happening around us. Those individuals that dare to name the reality often become outcasts in the society. The seers are condemned and vilified.

We carry with us a sort of “sick mania for hope,” says Hedges. If news isn’t positive or hopeful, we dismiss it or deny it. The majority of the population of a civilization in decline simply don’t want to hear the truth about the situation because the future seems too bleak. If you take just the issue of climate change, Chris explains, you can see that we live with two illusions: One, that it doesn’t exist; or two, that we can adapt. While most of us are hiding out in denial, according to Nietzsche, Chris reminds me, it is the role of intellectuals and artists, to see and confront the reality through their work.

“When you don’t confront the perils around you; when you build psychological mechanisms or walls—which we have done with the aid of technology and the aid of culture, then you’re almost guaranteed to commit collective suicide, Hedges tells me, adding, “The consequences …for my children and for future generations is catastrophic because if we don’t radically reconfigure our relationship to each other and to the earth, we are going to have to begin to confront the extinction of the human species.”

Yes, for so many reasons, one can see why some people have described Chris Hedges as “dark.” Having written my own dissertation at Pacifica on a phenomenon I termed “culture collapse disorder,” I spent many long hours contemplating the darkness of some of these same ideas. I remember Buddhist eco-scholar Joanna Macy writing that we, as humans, collectively live in fear of confronting the despair that we all carry—a despair that derives from dread of realizing for the first time that the human species may not pull through.[1]

“There is a kind of subterranean understanding the the ground is shifting in incredibly dramatic ways,” Chris agrees, but we certainly have our ways of coping and shoring up our denial. Our society has built mechanisms of indoctrination around consumerism and entertainment. Technology, he suggests, rather than being a boon for consciousness, has instead served to shut down the most basic understanding of who we are as individuals and as a society.

“There is a kind of subterranean understanding the the ground is shifting in incredibly dramatic ways,” Chris agrees, but we certainly have our ways of coping and shoring up our denial. Our society has built mechanisms of indoctrination around consumerism and entertainment. Technology, he suggests, rather than being a boon for consciousness, has instead served to shut down the most basic understanding of who we are as individuals and as a society.

Hedges introduces the term “atomization,” utilized by twentieth century political philosopher Hannah Arendt to describe how communal organizations (including bowling leagues and stamp clubs) have been obliterated in our culture, and how people have retreated into their own narrow circles and cut themselves off from establishments that made participatory democracy possible. Fewer and fewer people are showing up to churches and historical societies these days, he points out. With atomization comes a dangerous “cult of the self” which seeps into every aspect of our lives—including spirituality.

In the course of our conversation, I am reminded of something James Hillman once penned, writing:

Soul-making must be reimagined. We have to go back before Romanticism, back to medieval alchemy and Renaissance Neoplatonism, back to Plato, back to Egypt, and also especially out of Western history to tribal animistic psychologies that are always mainly concerned, not with individualities, but with the soul of things (“environmental concerns,” “deep ecology,” as it’s now called) and propitiatory acts that keep the world on its course.[2]

It’s a question of a society that honors the sacred—as pre-moderns did, Chris responds when I read Hillman’s words. Nothing has an intrinsic value in a corporate-capitalistic society. Everything has an exclusively monetary value, including human beings and the natural world, which we exploit until exhaustion or collapse. Chris cites Karl Polanyi’s work, The Great Transformation, in which Polanyi states that these societies have built within them their own self-annihilation, and points out that Polanyi, although he is an economist, actually uses the term “sacred” in his writings. In Hedges’ opinion, we have lost both the capacity to understand the sacred and the capacity for reverence for the sacred, resulting in the destruction of the very forces that sustain the earth and the community.

So, I wonder aloud: How do we reconnect with the sacred?

Chris doesn’t hesitate. Severance with natural world is a big part of the problem, he contends, and intrusions like television and Internet have fed the decay, disintegration, desensitivity and numbness of the wider culture. We have to find ways to unplug and find our way back to nature. Nature is what allows us to realize we are not the center of the universe. We’ve also lost connection with the voices of our ancestors, who can free us from the trap of modernity. We need to be able to reflect on what it means to have a life of meaning and to participate within a society. When we’re cut of from those voices, then in many ways we’re cut of from what it means to be human.

Chris doesn’t hesitate. Severance with natural world is a big part of the problem, he contends, and intrusions like television and Internet have fed the decay, disintegration, desensitivity and numbness of the wider culture. We have to find ways to unplug and find our way back to nature. Nature is what allows us to realize we are not the center of the universe. We’ve also lost connection with the voices of our ancestors, who can free us from the trap of modernity. We need to be able to reflect on what it means to have a life of meaning and to participate within a society. When we’re cut of from those voices, then in many ways we’re cut of from what it means to be human.

I can’t agree more with this diagnosis. It is at the heart of what I understand from my own studies in depth psychology. Our best hope to weather the coming storm and stay centered through the disintegration of society as we know it is to reconnect with those powerful forces that give us context and meaning, and to continually contemplate what Jung himself once wrote: “The decisive question for man is: Is he related to something infinite or not? That is the telling question of his life.”[3]

Listen to the full interview with Chris Hedges here (Approx. 33 mins.)

[1] Joanna Macy, “How to Deal with Despair.” Originally published in New Age magazine, June 1979

[2] James Hillman and Michael Ventura, We've Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy—and the World's Getting Worse, p. 51

[3] C. G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, pp. 356-7

Chris Hedges, M.Div., whose column is published weekly on Truthdig.com.com, has written 11 books, including the New York Times best seller Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt; Death of the Liberal Class; Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle; I Don't Believe in Atheists; and the best selling American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America. His book War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction. Hedges previously spent nearly two decades as a foreign correspondent in Central America, the Middle East, Africa and the Balkans and was part of the team of reporters at The New York Times awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 2002 for the paper's coverage of global terrorism. Hedges is a senior fellow at The Nation Institute in New York City. He has taught at Columbia University, New York University, Princeton University and The University of Toronto. He currently teaches prisoners at a maximum-security prison in New Jersey.

Bonnie Bright, Ph.D., graduated from Pacifica’s Depth Psychology program after defending her dissertation in December 2014. She is the founder of Depth Psychology Alliance, a free online community for everyone interested in depth psychologies, and of DepthList.com, a free-to-search database of Jungian and depth psychology-oriented practitioners. She is also the creator and executive editor of Depth Insights, a semi-annual scholarly journal, and regularly produces audio and video interviews on depth psychological topics. Bonnie has completed 2-year certifications in Archetypal Pattern Analysis via the Assisi Institute; in Technologies of the Sacred with West African elder Malidoma Somé, and has been extensively involved in Holotropic Breathwork™ and the Enneagram.

Bonnie Bright, Ph.D., graduated from Pacifica’s Depth Psychology program after defending her dissertation in December 2014. She is the founder of Depth Psychology Alliance, a free online community for everyone interested in depth psychologies, and of DepthList.com, a free-to-search database of Jungian and depth psychology-oriented practitioners. She is also the creator and executive editor of Depth Insights, a semi-annual scholarly journal, and regularly produces audio and video interviews on depth psychological topics. Bonnie has completed 2-year certifications in Archetypal Pattern Analysis via the Assisi Institute; in Technologies of the Sacred with West African elder Malidoma Somé, and has been extensively involved in Holotropic Breathwork™ and the Enneagram.